Working for a company in American Fork, Utah can be a rewarding experience. However if you’re a whistleblower employee, chances are you may be discriminated by your employer. However there are laws in place to protect you.

In 1989, Congress statutorily created a new standard of proof applicable in whistleblower cases, commonly referred to as the “contributing factor” test. This standard was directly incorporated into the Sarbanes-Oxley corporate whistleblower law (SOX). The test was designed by Congress to make it easier for whistleblowers to win their cases. If you are a whistleblower employee facing discrimination at work, speak to an experienced American Fork, Utah corporate lawyer.

The standard of proof set by Congress or the courts can be extremely significant. As the U.S. Supreme Court recognized, the standard “instruct(s) the factfinder” regarding the “degree of confidence our society thinks” needs to be established concerning the “correctness of factual conclusions.”

Most civil cases are adjudicated on the “preponderance of the evidence” standard, in which litigants “share the risk of error in roughly equal fashion.” In SOX cases, the traditional “preponderance of evidence” standard was modified in order to make it easier for whistleblowers to prove their cases, reflecting the “society’s” interest in ensuring adequate protection for employees who risk significant adverse action for having the courage to blow the whistle.

When Congress first developed the “contributing factor” test, its intent to modify the traditional burdens of proof in employment cases was crystal clear. Congress wanted to make it “easier for an individual to prove that a whistleblower reprisal has taken place.”

The “contributing factor” test sets forth a statutory mechanism governing the burdens of proof in whistleblower cases. The often conflicting or confusing burdens of proof set forth in numerous judicial decisions under other employment discrimination laws were replaced by a statutory formula. Under this formula, an employee has the burden of proof to establish the following:

1. That she or he is an employee covered under the SOX;

2. That she or he engaged in activities protected under the SOX;

3. That the employer was aware of this protected activity;

4. That the protected activity was a “contributing factor” in an adverse action taken by the employer.

5. Once the employee demonstrates a “contributing factor,” the burden of proof shifts to the defendant to establish, by “clear and convincing evidence,” that the employer would have taken the same adverse action even if the employee never engaged in protected activity.

Once an employee demonstrates that discriminatory animus was a “contributing factor” to an adverse action, the burden of proof shifts to the employer to demonstrate, by “clear and convincing evidence,” that the employer would have taken the same adverse action even if the employee had not engaged in whistleblowing activity. The “clear and convincing evidence” test is “tough standard” for employers. Congress intended that employers “face a difficult time defending themselves” in whistleblower cases. In order to meet the “clear and convincing” standard, an employer must establish its defense by evidence stronger than a mere “preponderance” of the evidence. The level of proof needed to meet this standard is usually explained as “highly probable.

Proof of Discrimination

The heart of a SOX whistleblower case rests in demonstrating that protected activity was a “contributing factor” in an adverse action. A “contributing factor” may be demonstrated through direct or circumstantial evidence. It is well settled and established that employers will rarely if ever, directly admit that protected activity contributed in any manner whatsoever to an adverse action. The typical case scenario requires a court or jury to weigh various subtle facts or admissions and determine whether these circumstances demonstrate that discrimination “contributed” to an adverse decision. A “contributing factor” may be proven by either direct or circumstantial evidence. Likewise, direct evidence of retaliatory motive is not needed in either a “pretext” or a “mixed motive” case.

Direct Evidence

Exactly what constitutes “direct evidence” of animus has been the subject of a number of differing definitions. It is commonly defined as evidence that, if believed, “proves the existence” of a disputed fact “without inference or presumption.” Put another way, “direct evidence” is “evidence that directly reflects the use of an illegitimate criterion in the challenged decision” or “actions or remarks” that tend to “reflect a discriminatory attitude” and are related to the “decisional process.”

Obtaining such evidence in an employment case is very difficult. Most employers do not admit to discriminating against employees, and “smoking gun” documents exist only in rare cases. Consequently, as a matter of law, it is “improper to require plaintiffs to produce direct evidence of discriminatory intent in order to prevail at trial” in a whistleblower case. Not only is direct evidence of discrimination not required, the Supreme Court has recognized that circumstantial evidence “is not only sufficient” to prove a case but, in some instances, may be even more “persuasive than direct evidence.”

Circumstantial Evidence

In the majority of cases, employees rely upon circumstantial evidence to demonstrate discriminatory motive or evidence that protected activity was a “contributing factor” for the adverse action. Circumstantial evidence is “often the only means available to prove retaliation claims. Moreover, evidence that an employer’s justification for an adverse action is untrue may itself constitute “persuasive” circumstantial evidence of “intentional discrimination.” These general principles of legal analysis are applied to SOX whistleblower cases.

Some of the factors that have been used successfully to establish circumstantial evidence of discriminatory motive in whistleblower cases are:

• Work Performance: high work-performance rating prior to engaging in protected activity, and low rating or problems thereafter, absence of previous complaints against employee.

• Timing: The timing of an adverse action (i.e., discipline or termination shortly after the employee engaged in protected activity).

• Disparate Treatment: Treating a whistleblower differently from a non-whistleblower.

• Deviation from Procedures: Deviation from routine procedure; manner in which the employee was informed of adverse action or the inadequate investigation or review of a disciplinary decision; absence of warning before termination or transfer; pay increase shortly before termination; a pattern of “suspicious circumstances” or a “suspicious sequence of events” surrounding the discipline of an employee.

• Attitude: Attitude of supervisors toward whistleblowers; charges of “disloyalty” or other derogatory remarks concerning protected activity; low regard for corporate oversight personnel.

• Pretext: Failure of the company to prove allegations, contradictions or shifting explanations in an employer’s explanation of the purported reasons for the adverse action; proof that the purported reason for taking an adverse action is not true or believable, the magnitude of the alleged offense.

• Antagonism to Protected Activity: Reference to an employee engaged in protected activity as a “troublemaker” or an otherwise “unfavorable attitude” toward employees who reported violations; antagonism toward a “regulatory scheme;” anger, antagonism, or hostility toward complainant’s protected conduct; a pattern of antagonism.

• What an Employee Exposed: Evidence that the whistleblower’s concerns were correct and the potential magnitude of the problem identified by the employee

• Dishonesty: Dishonesty regarding a “material fact.”

This list of factors is not exhaustive.

Timing

One of the most common factors used to establish motive is timing: “Adverse action closely following protected activity is itself evidence of an illicit motive.” The fact that an employer takes disciplinary action shortly after an employee engages in protected activity is, unto itself, usually “sufficient to raise an inference of causation” and establish that element of the prima facie case. Timing can be relevant not only as support for a prima facie case but also as evidence supporting an ultimate finding of discrimination: “Disbelief of the reasons proffered by a respondent “for an adverse action” together with temporal proximity may be sufficient to establish the ultimate fact of discrimination.”

Pretext

Proving that the reason given by an employer for taking adverse action was false (or a pretext) can be critical evidence demonstrating discrimination.

Unquestionably, demonstrating that the reason an employer gave for an adverse action is not believable can be compelling evidence, both of the fact that an employer had a discriminatory motive and that the employer cannot meet its burden of proof. Common sense would dictate this result. If an employee is a whistleblower, and the employer lies about the reason for an adverse action, the employee will almost always win the case.

Disparate Treatment

Evidence of “disparate treatment” is also “highly probative evidence of retaliatory intent.” Disparate treatment simply means that an employee who engages in protected activity was treated differently, or disciplined more harshly, than an employee who committed a similar infraction and did not engage in protected activity.

Where a disciplinary response clearly does not fit with the type of infraction at issue, an inference of discrimination may be demonstrated. Likewise, evidence that the employer “orchestrated” justifications for a termination is evidence of discrimination. However, absent proof of discriminatory motive, courts “do not sit as a super-personnel department” and second-guess employment decisions. Corrective action is warranted only if an employee can demonstrate that discriminatory animus played a role in the decision, regardless of how “medieval” a firm’s practices or “mistaken” a manager’s decision.

The Complaint

Unlike a civil action filed in federal court, an employee is under no obligation to serve his or her initial complaint on the employer. Instead, after the complaint is filed, OSHA is required to serve a copy of the complaint or other information related to the filing of the complaint upon both the employer and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The complaint is deemed filed when mailed, e-mailed, faxed, or filed in person at a DOL OSHA office.

The complaint must be written, can be simple, and should include a full statement of the acts and omissions, with pertinent dates, that are believed to constitute the violation. A Department of Labor whistleblower complaint need not set forth “every element of a legal cause of action.” Although the initial complaint can be simple, an employee should fully augment or supplement the basis for the complaint during the OSHA investigatory process. Employers have relied upon limitations in the complaint as a basis for filing motions for dismissal once a case is docketed for a formal administrative adjudication. Although the initial complaint can be simple, an employee should fully augment or supplement the basis for the complaint during the OSHA investigatory process. Employers have relied upon limitations in the complaint as a basis for filing motions for dismissal once a case is docketed for a formal administrative adjudication. The traditional practice during the OSHA investigatory process is for an employee to supplement his or her complaint with a formal signed statement provided to the OSHA investigator. This practice is reflected under the DOL rules for SOX investigations. Under these rules, after a complaint is filed, the complaint may be “supplemented as appropriate by interviews of the complainant.”

Statute of Limitations

A SOX case must be filed within 90 days of the alleged discriminatory action. The failure to comply with this deadline will result in the dismissal of a complaint, regardless of the underlying merits of the claim. However, because a statute of limitations is “not jurisdictional” in nature, under limited circumstances an employee’s deadline for filing a claim “may be extended when fairness requires.” If an employee fails to file a claim within the 90-day statute of limitations, there are a limited number of methods by which the filing deadline may be enlarged. But the grounds for extending a limitations period are “narrowly applied.” The basic theories used to enlarge a filing period are equitable tolling, equitable estoppel, fraudulent concealment, or continuing violation.

After a complaint is filed, OSHA will typically assign the case to a field office investigator. The investigator will review the complaint and its supporting materials in order to ensure that the employee has alleged a prima facie case. If an employee cannot allege the elements of a cause of action, OSHA will terminate its investigation and issue a finding of dismissal. Before dismissing a complaint, the OSHA investigator will contact the employee and determine whether the complaint can be supplemented by additional information in order to meet the prima facie case requirements. The OSHA investigator will review the materials submitted by the complainant (including the statement provided by the employee) and determine if the allegations were sufficiently pled.

If you believe you need legal help from a business attorney, call to speak to an experienced American Fork, Utah corporate lawyer today.

American Fork Utah Corporate Lawyer Free Consultation

When you need legal help with your business, company, LLC, corporation or partnership, please call Ascent Law for your free consultation (801) 676-5506. We want to help you.

8833 S. Redwood Road, Suite C

West Jordan, Utah

84088 United States

Telephone: (801) 676-5506

Recent Posts

Corporate Lawyer North Salt Lake Utah

Brachial Plexus Injury Lawyer in Utah

Investment In Foreign Real Estate Lawyer

Ascent Law LLC St. George Utah Office

Ascent Law LLC Ogden Utah Office

American Fork, Utah

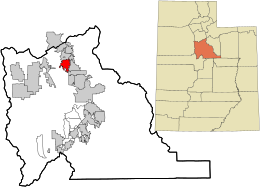

American Fork is a city in north-central Utah County, Utah, United States, at the foot of Mount Timpanogos in the Wasatch Range, north from Utah Lake. This city is thirty-two miles southeast of Salt Lake City. It is part of the Provo–Orem Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 33,337 in 2020.[5] The city has grown rapidly since the 1970s.

[geocentric_weather id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_about id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_neighborhoods id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_thingstodo id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_busstops id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_mapembed id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_drivingdirections id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_reviews id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]