Never fight a criminal trial without the assistance of an experienced American Fork Utah criminal lawyer. Criminal trial is a complex process and best left to the experts.

The first step at trial is the opening statements. There are several purposes for the opening statement. One is to inform the jury about the case. A second is to persuade the jury about the merits of the case. A third is to try to gain sympathy from the jury. If the opening statements are clear, they will provide the jurors with a road map for the rest of the trial, making it easier for them to follow the evidence. By law, the prosecution is always the first to give an opening statement in criminal trials. The prosecution is followed by the defense counsel, but the defense counsel does not have to give an opening statement, or may postpone it until after the prosecution has rested its case.

Although most judges give wide latitude to attorneys in the presentation of opening statements, there are some basic rules concerning what can be included. All facts that an attorney can prove at trial can be included in opening statements. An attorney will want to include the major facts of the case in order to provide an overview of what the jury should pay attention to throughout the trial. Although it will be the duty of the judge to explain the applicable law to the jury before it begins its deliberations, the attorneys may make short references to the law to help the jury understand their case. For example, either attorney may want to explain the burden of proof in the case or the elements that must be proven in order for the jury to convict. While attorneys are not allowed to make arguments in their opening statements, they may present theories about the case at this time. Any theory must be prefaced by remarks such as, “The evidence will show,” but attorneys are not allowed to draw conclusions without placing those conclusions within the context of facts that will be developed at trial. Conclusions and arguments about what the evidence has shown are reserved for closing arguments—after all evidence has been presented.

Direct Examination

In criminal trials, the prosecution is the first to present its case. This is done primarily through the presentation of witnesses subjected to direct examination. Attendance of witnesses may be either voluntary or by command of the court. If attorneys believe that a witness may not voluntarily make an appearance at the trial, they may subpoena the individual, compelling the witness to appear. Once the subpoena is served, the witness must testify or risk being found in contempt of the court and punished for that contempt. Attorneys can also obtain a subpoena duces tecum in order to command that documents be brought to trial to be entered into the record.

In direct examination, an attorney calls a witness and after she swears to tell the truth, the attorney attempts through questioning to draw out the relevant facts to allow the fact finder to reach the desired verdict.

Direct examination has two primary goals—to make testimony clear to the fact finder and to make it memorable. When considering what to include in direct testimony, attorneys planning their strategy for trial must strike a delicate balance, presenting a full factual picture that advances a strong argument to achieve the desired result, but not dizzying the jury with so many facts that they become bored and quit paying attention. In order to balance these two concerns, attorneys must keep a sharp eye on the issue of relevance and ask whether the introduction of additional evidence is really necessary to prove their case. As noted earlier, attorneys must also decide in what order to present witnesses and evidence. The order can be crucial to making the evidence memorable. Evidence must be given to the fact finder in an order that is understandable and that makes sense.

Direct testimony is given through a series of questions presented by the attorney, followed by the answers of the witnesses. This format limits the testimony to those items that are relevant to the case. Questions can take a variety of forms, which widen or narrow the latitude given to witnesses in their answers. Open, narrative questions allow witnesses a great deal of freedom to tell their own story. Narrative questions often enhance the credibility of a witness, since the fact finder sees that witnesses are telling the story in their own words. However, when asking narrative questions, the attorney must make sure that the witness stays on track and does not digress, boring the fact finder.

In contrast to narrative questions, closed questions are worded so as to place limits on the witness’ response. The purpose of a closed question is to elicit a particular fact from the witness.

Generally, the attorney who calls the witness for direct examination cannot ask leading questions. Leading questions typically can be answered with a simple yes or no. This form of direct examination would not be allowed, since it suggests an answer and effectively gives the attorney—rather than the witness—an opportunity to testify. One is to draw the fact finder’s attention to negative character traits that may influence witnesses’ willingness to tell the truth, such as exposing past criminal convictions. A second is to demonstrate that witnesses have biases, interests, motives, or prejudices that may interfere with their ability to be objective. If attorneys believe that a witness’ version of the facts supports their case, that’s another reason to conduct a cross-examination. In that case, they will seek to cross-examine on those points in order to bolster their arguments.

The scope of questioning allowed during cross-examination differs from that allowed during direct examination. For example, the scope of questioning in cross-examination is narrower, usually limited to issues that came out during direct examination. One exception is the attempt to attack the credibility of a witness. As with other aspects of which evidence is allowed at trial, the judge determines the latitude of the scope of questioning in cross-examination. If a judge will not allow attorneys to investigate new areas with a witness during cross-examination, that witness can later be called for direct examination by those attorneys. An attorney can also attack the credibility of a witness by calling on direct-examination character witnesses to testify against a witness’ integrity.

Another difference between direct- and cross-examination is that during cross-examination an attorney can ask leading questions. Leading questions in cross-examination are preferred because it allows the attorney to control the flow of information by not allowing the witness to interject voluntary statements that may harm the attorney’s strategy.

Despite strong reasons not to use them, open questions can be asked during cross-examination and are sometimes used when an attorney has nothing but suspicions and finds it necessary to go on a fishing expedition. Such questions, do, however, present dangers.

Redirect Examination

After an attorney has cross-examined an adverse witness called by the opposing attorney, the attorney who initially called the witness has an opportunity for redirect examination. The scope of the redirect examination is limited to those subjects brought out in cross-examination. The purpose of redirect examination is to clarify any discrepancies in the testimony that may have been brought up during cross-examination or to rehabilitate the credibility of the witness. In this way, any doubts created in the jury’s mind about the witness or her testimony will hopefully be resolved. When redirect examination is completed, the opposing counsel has the opportunity to recross-examine the witness. Once again, the scope of this examination, if it takes place, is limited only to those subjects brought out in redirect examination. This process of narrowing the scope of examination can continue until neither side has further questions or the judge believes that it is no longer useful.

The Defense Case

When the prosecution finishes presenting its case, it is the defense attorney’s opportunity. Prior to presenting their own case, defense attorneys will often, as a matter of form, ask for a directed verdict from the judge. This is a request for the judge to declare that the prosecution did not present sufficient evidence for a prima facie case to be made against the defendant. The defense attorney then asks the judge to declare that the trial cannot continue and the defendant must be declared not guilty of the charges. Judges rarely grant motions for directed verdicts, so the defense is forced to proceed with its own case. The presentation of the defense case follows the same process as that of the prosecution. It starts with the defense calling its witnesses for direct examination; the prosecution then has the opportunity for cross-examination, followed by redirect and recross until the attorneys are satisfied.

The defense attorney has one decision to make that presents special problems not confronted by the prosecution. That is whether the defense should call the defendant as a witness. Due to the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, defendants cannot be forced to testify. The decision to testify is left up to the defendant in consultation with counsel. This is a difficult decision to make. On the one hand, the jury expects to hear a claim of innocence from the defendant to help in assessing the evidence. If the defendant in a criminal case doesn’t testify, jurors may draw inferences about the defendant’s guilt based on his unwillingness to testify, despite warnings not to from the judge. On the other hand, the defendant does court danger by testifying. The danger comes because, as with all witnesses, the defendant will be subjected to cross-examination. Not only can prosecutors question a defendant’s rendition of events, they can also try to impeach the defendant’s credibility by introducing evidence of his past criminal record.

Closing Arguments

After the attorneys on both sides have had a chance to submit proposed jury instructions to the judge, the judge will determine the instructions of law that will be given to the jury. Prior to closing arguments, the judge informs the attorneys about the content of the instructions. In writing their closing arguments, attorneys must adhere to the instructions that the judge will give to the jury. This is because the elements of the law that must be proven in order for a guilty verdict to be returned will be found in the instructions. If an attorney disregards the instructions and presents an alternative description of the law, the judge will tell the jurors to disregard that interpretation. Such a situation would harm the attorney’s credibility at a pivotal point in the trial, so attorneys closely read the judge’s instruction prior to giving their closing arguments. Closing arguments give attorneys for both sides a final chance to summarize their view of how the case should be resolved and why.

The closing argument, prepared in advance of trial, provides the focus, structure, and themes for the entire trial process including preparation. The entire case points to the final argument and should be prepared and presented to be consistent with the closing. The focus, structure, and themes of the final argument will be those used in preparation, voir dire, opening, direct, and cross-examination. Final argument is the attorney’s last opportunity to summarize for the fact finder what the evidence has shown the facts to be in the case. Summation is the most effective occasion in the trial to explain to the jury or judge the significance of the evidence. The closing is the time when the creative lawyer can draw inferences, argue conclusions, comment on credibility, refer to common sense, and explain implications which the fact finder may not perceive. Final argument is the only chance the attorney will have to explain and comment on the judge’s instructions of the law and to weave the facts and law together. Summation is the attorney’s last opportunity to urge the fact finder to take a specific course of action.

The content of closing arguments is broad. Closing arguments do not constitute evidence; they are legal arguments. Attorneys will seek to explain the issues that are relevant in the case and highlight testimony that is beneficial to their side, while pointing out weaknesses in the other side’s assessment of the case. In doing so, the attorneys can remind the jurors about perceived credibility problems in the witnesses who testified. The attorneys will attempt to take the evidence that was brought out in the trial and instruct the jury on the inferences that can be drawn from the evidence. The attorneys are allowed to point out to the jury the conclusions that can be drawn from the evidence and urge that a verdict be reached based on these inferences and conclusions. Attorneys will not limit their closing arguments to the evidence brought out at trial; they will also attempt, at times, to include emotional appeals to the jury. As legal arguments, attorneys are granted great leeway in the scope of their summations. The prosecution is allowed to first present its closing argument, followed by the defense, and then a final rebuttal by the prosecution, which is normally limited to addressing those issues discussed by the defense attorney.

Being charged with a criminal charge or being arrested in the Atlanta area can be extremely stressful. You require a lawyer who will fight and get the charges dismissed. You may feel that you do not have a defense. Your entire future is at stake. Act now to avoid being convicted. Don’t waste any more time. Contact an experienced American Fork Utah criminal defense lawyer.

American Fork Utah Criminal Defense Lawyer Free Consultation

When you need legal help with a criminal case in American Fork Utah, please call Ascent Law today for your free consultation (801) 676-5506. We want to help you.

8833 S. Redwood Road, Suite C

West Jordan, Utah

84088 United States

Telephone: (801) 676-5506

Recent Posts

Get Your Employees CPR and First Aid Certified

Real Estate Lawyer Bluffdale Utah

Tips For Surviving Divorce Settlement Talks

Ascent Law LLC St. George Utah Office

Ascent Law LLC Ogden Utah Office

American Fork, Utah

|

American Fork

|

|

|---|---|

The old city hall is on the National Register of Historic Places.

|

|

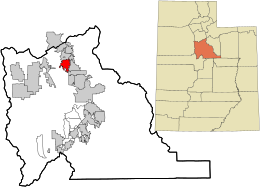

Location in Utah County and the state of Utah

|

|

| Coordinates: 40°23′3″N 111°47′31″WCoordinates: 40°23′3″N 111°47′31″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Utah |

| Settled | 1850 |

| Incorporated | June 4, 1853 |

| Named for | American Fork (river) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.16 sq mi (28.90 km2) |

| • Land | 11.15 sq mi (28.87 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation

|

4,606 ft (1,404 m) |

| Population

(2020)

|

|

| • Total | 33,337 |

| • Density | 2,987.19/sq mi (1,154.73/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code |

84003

|

| Area codes | 385, 801 |

| FIPS code | 49-01310[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1438194[4] |

| Website | www |

American Fork is a city in north-central Utah County, Utah, United States, at the foot of Mount Timpanogos in the Wasatch Range, north from Utah Lake. This city is thirty-two miles southeast of Salt Lake City. It is part of the Provo–Orem Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 33,337 in 2020.[5] The city has grown rapidly since the 1970s.

[geocentric_weather id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_about id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_neighborhoods id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_thingstodo id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_busstops id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_mapembed id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_drivingdirections id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]

[geocentric_reviews id=”f9bf6a63-bf88-44b0-b78b-971b613889ca”]